Although it’s named the Fiscal Responsibility Act, the compromise debt ceiling package that President Joe Biden signed into law this past weekend doesn’t do much to fix the nation’s enormous financial challenges.

The deal, which prevented the US from defaulting on its obligations and unleashing economic upheaval, holds non-defense discretionary spending relatively flat for the coming fiscal year after agreed-upon appropriations adjustments and allows an increase of only 1% the following fiscal year. It temporarily expands work requirements in the food stamps program and rescinds more than $21 billion in funding for the Internal Revenue Service.

All told, it would reduce budget deficits by about $1.5 trillion over the coming decade, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

However, the nation’s fiscal problems are far bigger than that – mainly because the federal government spends much more than it takes in in revenue.

Here are a few scary statistics:

- The federal budget deficit for 2023 alone is projected to be $1.5 trillion, and it will nearly double to $2.7 trillion in 2033, according to the CBO’s most recent analysis. The cumulative deficit over the coming decade is estimated to be $20.2 trillion.

- Measured in relation to the size of the economy, deficits will grow from 6% of gross domestic product next year to 6.9% in 2033, which is far above their 50-year average of 3.6% of GDP, the CBO forecasts.

- That imbalance is also causing the debt held by the public to soar, jumping from 98% of GDP at the end of this year to 119% at the end of 2033, which would be the highest level ever recorded, the agency said.

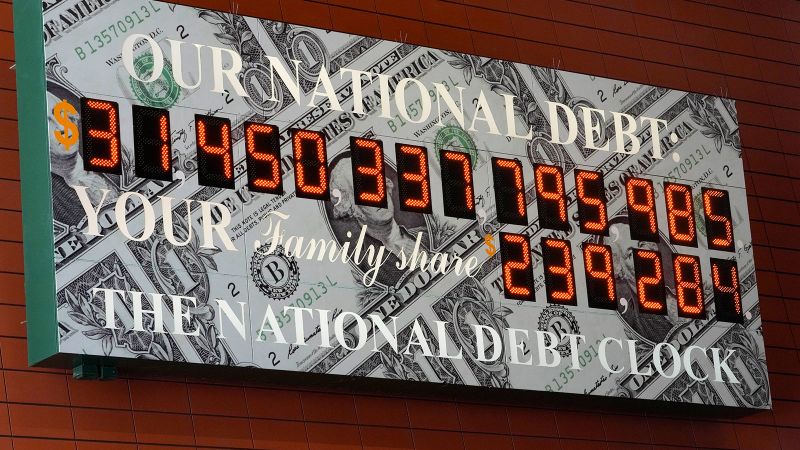

- The nation hitting its $31.4 trillion debt ceiling in January prompted Biden and House Republicans to scramble to cobble together a package both parties would approve. In 2033, that figure will be $52.4 trillion, the CBO projects.

- During the next decade, spending on programs that provide benefits to the swiftly growing number of older Americans – primarily Social Security and Medicare – will skyrocket, as will interest costs. By 2033, outlays for Social Security, the major health care programs and interest will make up 65% of spending, the agency estimates.

But Biden vowed to keep Social Security and Medicare out of the negotiations on the debt ceiling and budget cuts, which House Republicans agreed to. This step meant that the spending reductions focused on a fairly small sliver of the federal budget.

“For any serious effort to address our long-term fiscal challenges, everything needs to be on the table, especially the drivers of the debt,” said Michael Peterson, CEO of Peter G. Peterson Foundation, a nonpartisan organization that promotes ways to put the US on a more sustainable fiscal foundation.

Those drivers include spending on mandatory programs like Social Security and Medicare and the lack of sufficient tax revenues. Social Security accounted for about 19% of federal spending in fiscal 2022, while Medicare took up 12%, according to US Treasury Department data.

At least one longtime budget watchdog is somewhat more optimistic about the debt ceiling package, estimating it will generate between $1 trillion and $2 trillion in savings over the next 10 years and pointing out that it places caps on discretionary spending for the next two years.

If the US could save $8 trillion over the next decade, it would be in decent shape, said Marc Goldwein, the senior policy director for the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. The Fiscal Responsibility Act gets the nation one-eighth to one-quarter of the way there.

“That’s not nothing. That’s substantial,” he said. “But that’s clearly not enough to get us all the way there or even most of the way there.”

There’s still room to cut discretionary spending, which is up 37% since 2017, Goldwein noted. But the savings can’t all come from non-defense discretionary spending. Congress and the president will have to look at the rest of the budget and at the tax code to stabilize the debt – areas politicians are loath to touch.

“The bottom line is we’ve promised to spend too much and tax too little,” he said.

Read the full article here