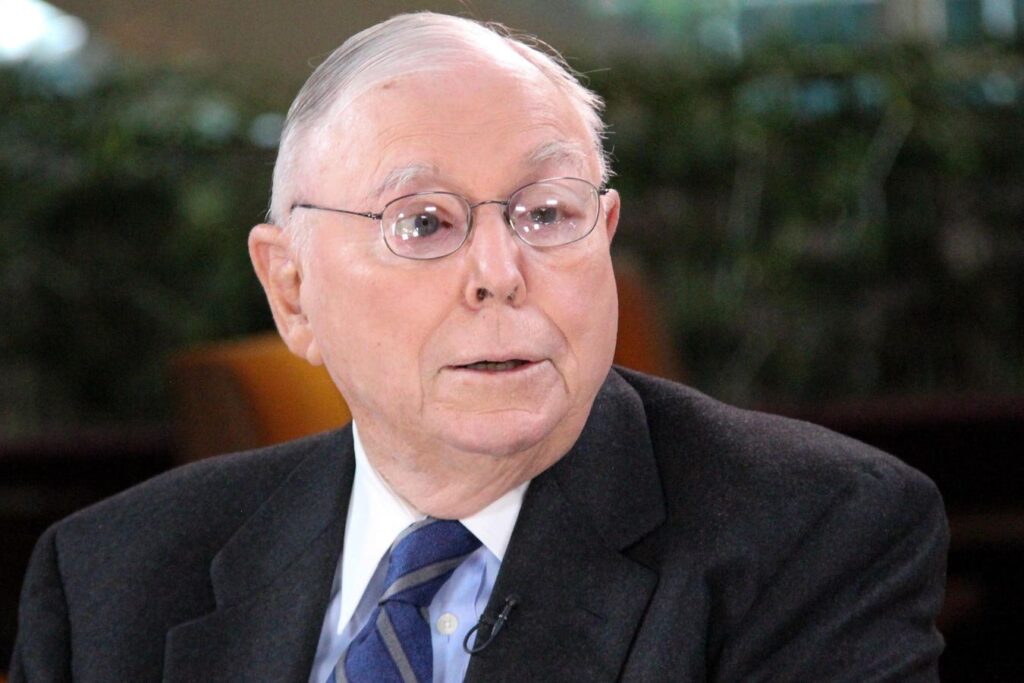

The world lost an investment legend and font of knowledge last week with the passing of Charlie Munger at the age of 99. He was best known as Warren Buffett’s partner in building Berkshire Hathaway from its humble roots as a New England textile maker into the ninth largest company in the S&P 500. Interestingly, Munger was a force beyond just investing as an advocate for lifelong learning and rational decision-making.

He was crucial in the Berkshire becoming as large as it has become. Munger helped evolve Buffett’s investment style from buying companies akin to “cigar butts” with one more puff in them at very low valuations to high-quality businesses at a reasonable price. While Buffett would have likely eventually reached that conclusion on his own, Munger certainly sped up the progression, which made a difference in compounding the value of Berkshire Hathaway. These “quality” fingerprints can be seen in Berkshire’s original purchase of See’s Candies and on to Coca-Cola (KO) and Apple (AAPL).

Beyond his investing acumen, Munger will be remembered for his blunt and entertaining style of wit and wisdom. He tried to fashion his life after his hero, Benjamin Franklin, succeeding as a polymath and dispensing timeless wisdom. One of his most valuable tools was mental models, shortcuts to explaining how the world works and making rational decisions. Among his guiding principles were preparation, patience, discipline, and objectivity.

One handy tool that Munger often spoke about for solving complex problems came from German mathematician Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi. He wrote, “Man muss immer umkehren,” which means, in Munger’s shorthand, “Invert, always invert.” In other words, reversing the problem can aid in figuring out a solution. For example, how do you select an investment manager who will outperform in the future? Inverting the question is, how do you choose an underperforming investment manager? Part of that answer is easy as a weak investment process and picking the best-performing manager over the last three years will likely lead to poor outcomes. So now, some of the answers become clear: at the minimum, you should not focus on short-term results but look for a robust investment process.

Additionally, for best results in investing and life, one should stay within their “circle of competence.” In other words, you should only compete or invest in areas where you know what you are doing and have a competitive advantage. This methodology has the added advantage of being a risk-mitigating technique. It also allows one not to waste time and energy on questions or investments outside your circle and just put them on the “too hard pile.” While it takes effort, Munger would argue that one can and should expand their circle of competence. This principle drove Munger’s lifelong learning and becoming a better investor, even as he aged.

It would be wise to follow Charlie Munger’s own words, “You can learn a lot from dead people. Read of the deceased you admire and detest.” He certainly falls into the former category and would undoubtedly appreciate continuing to help foster rational behavior from the great beyond. An excellent place to start is with the book Poor Charlie’s Almanack, which contains many of the previously discussed lessons, and an updated edition is being released on Tuesday.

Read the full article here